Abstract

Child health in Ghana falls below global averages for child and infant mortality and is understudied in the Akatsi District of Eastern Ghana. In this study, a survey based assessment of the child health at 4 local public and private clinics in Akatsi was conducted over an 8 week period. Economic factors, accessibility issues, and common illnesses of children 0-5 years of age were assessed. The National Health Insurance Scheme and government-sponsored public health initiatives were found to be widely utilized. The most common illnesses reported were fever, cough, vomiting, and rash. Despite high enrollments in government programs and encouraging signs of growth in the health sector, much progress is needed to improve the rural health access and treatment options available to the children of this region.

Background

Ghana, a West African country of ~24 million people, is administratively divided into regions, which are then subdivided into districts. The Akatsi District is one of 15 districts in the Volta Region in Eastern Ghana and has a population of ~100,000 (see attached as Appendix I). The Akatsi District is primarily an agricultural district with a poorly developed education system. There is one private hospital and 18 health clinics in the district—13 public and 5 private. Child health in Ghana has been extensively studied in a variety of settings with a variety of foci.1,2,3 Health studies addressing the specific population of the Volta Region of Ghana, however, have been few. Studies have shown chronic ill-health due to under nutrition and anemia among school children.4 Parasitic infections have chronically plagued the population of the Akatsi District and have contributed extensively to poor child health and development.5 Gender roles in the region exert negative pressures on child health access in separate studies.6,7

The need for a better understanding of the health issues facing the child population is demonstrated by the childhood mortality rates among Ghanaian children. Despite a recent stagnation in childhood mortality, children in Ghana under the age of five die at a rate of 101 per 1000 live births.8 The global average is 80.3. Infant mortality rates are also above the global average.9 Despite the progress that has been made in Ghana, there is still much to accomplish. This study seeks to contribute to these efforts in the small district of Akatsi.

History of Collaboration

In September of 2007 I was asked to conduct a child health needs assessment in the Akatsi District of Ghana by Dr. Senyo Adjibolosoo—a native Ghanaian. Dr. Adjibolosoo is an economics professor at Point Loma Nazarene University and the founder of the Human Factor Leadership Academy (HFLA)—a private school in the Akatsi District that will be opening its doors in the fall of 2009. As part of the school, Dr. Adjibolosoo is planning to open a public health clinic to serve the needs of the greater Akatsi community. The health priorities of the region, however, have not been elucidated. I was asked to conduct an assessment to assist in determining the services that are currently needed. Under the close and continuing mentorship of an epidemiologist at my medical institution, Dr. Robert Ryder, and with the help of Greg Pollard, RN, a data collection instrument was designed and administered in the summer of 2008.

Data and Results

Of the 287 children surveyed, 49% are female and 51% male. Greater than 93% are enrolled in the Akatsi District Health Insurance Scheme, the national insurance program of Ghana. A majority of mothers have formal education through primary or junior high school and child vaccinations are reported in over 90% of eligible respondents. 88% of the children sleep under mosquito bed nets.

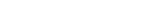

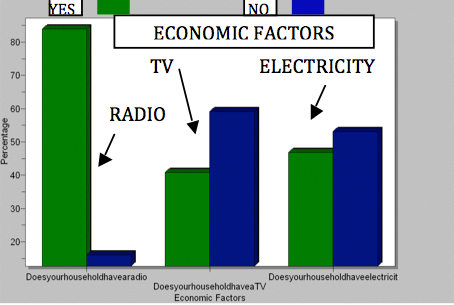

Socioeconomic factors surveyed showed 46% of households have electricity and 41% own televisions. Accessibility issues surveyed show that most children (44.3%) traveled 1-2.99km to reach the clinic. 13.6% traveled 5-10km, and 6.6% traveled greater than 10km.

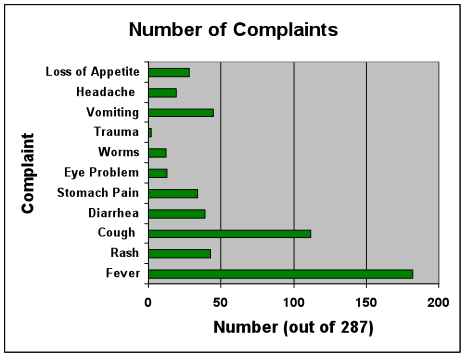

Among complaints given by mothers regarding their children (multiple could be cited), fever (63.4%), cough (39%), vomiting (15.7%), and rash (15%) were most common. Diarrhea (13.6%) and stomach pain (11.8%) were also cited. Surprisingly, trauma was rarely cited, with only 2 out of 287 children (0.7%) coming to the clinic with this complaint.

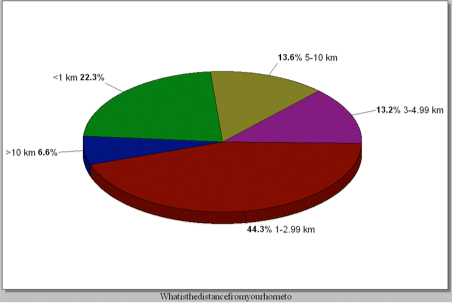

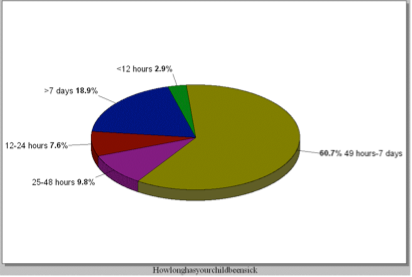

Most children waited between 48 hours and 7 days to visit the clinic (60.7%), with 18.7% waiting more than 7 days. 58.8% reported receiving treatment of some kind prior to arriving at the clinic, with 53.1% of those who received treatment being given drugs from a drugstore.

Conclusions

This survey brings to light many important factors surrounding the healthcare in Akatsi. Ghana in general has a very encouraging national health insurance scheme and vaccination program. While most children receiving treatment are covered under the insurance plan, it is unclear if many others not seen are prohibited from care due to lack of coverage. The Akatsi Health Insurance Scheme states that about 55-60% of the population of Akatsi is covered by the program. It is unclear if this percentage is reflective of the child population in the district as well. If indeed it is, there is a large disparity between the percentage of children in the district who are covered (55-60%) and the insurance coverage of the children who attended clinics during the survey period (>93%). One hypothesis to explain this disparity is that those who are not covered do not seek treatment at the clinics as frequently as those who are covered. Assuming both populations get sick with the same frequency, this is either because those who are covered are more likely to visit the clinic when well, or because those who aren’t covered are less likely to visit the clinic when sick. The later possibility must be addressed through expanded insurance coverage and government health programs for the poor.

Akatsi is a poor area by western economic standards; less than 50% of child households have electricity. While in the minority, some dwellings have thatch roofs and clay walls and floors, which contribute to damp living conditions and presumably poorer health outcomes when compared to those living in block houses with metal roofs.

It is important to remember that accessibility, especially in the rural areas, prohibits some from obtaining healthcare in a timely fashion. Some must travel in excess of 10km to reach the clinic, forcing families to take at least one full day, and often longer, to take a child to the doctor. This decreases the hours spent working, and thereby decreases overall household productivity.

Health complaints of the children range from fever to worms to loss of appetite. Trauma, surprisingly, is not a significant contributor to morbidity in the region. It is unclear if this is due to a low incidence or a lack of timely treatment, resulting in death. Also, alternative treatment options are common, although their affects on health outcomes are unknown. It may be important to do further research into these alternative methods, specifically the products obtained from drug stores. This was a common practice among those who provided treatment prior to arriving at the clinic among those with and without health insurance. It was not asked what was given or who decided what would be given, but these are important questions that could be explored.

The district of Akatsi has limited resources, but the healthcare provided, especially in the preventative setting, is encouraging and improving. Increased focus on accessibility and economic development in the rural areas is imperative to see continued health improvement in the children of the Akatsi district.

References

1.Gyasi, R. T., Y. (2007). Childhood Deaths from Malignant Neoplasms in Accra. Ghana Medical Journal, 41(2), 78.

2.Oduro, Abraham R Koram, Kwadwo A Rogers, William Atuguba, Frank Ansah, Patrick Anyorigiya, Thomas Ansah, Akosua Anto, Francis Mensah, Nathan Hodgson,Abraham Nkrumah, Francis. (2007). Severe falciparum malaria in young children of the Kassena-Nankana district of northern Ghana. Malaria Journal, 6, 96.

3.Reither, Klaus Ignatius, Ralf Weitzel, Thomas Seidu-Korkor, Andrew Anyidoho, Louis Saad, Eiman Djie-Maletz, Andrea Ziniel, Peter Amoo-Sakyi, Felicia Danikuu, Francis Danour, Stephen Otchwemah, Rowland N Schreier, Eckart Bienzle, Ulrich Stark, Klaus Mockenhaupt,Frank P. (2007). Acute childhood diarrhoea in northern Ghana: Epidemiological, clinical and microbiological characteristics. BMC Infectious Diseases, 7, 104.

4.The health and nutritional status of schoolchildren in Africa: Evidence from school-based health programmes in Ghana and Tanzania. The partnership for child development. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1998;92( 3):254.

5.Diamenu, S K Nyaku,A A. Guinea worm disease—a chance for successful eradication in the Volta region, Ghana. Social Science Medicine. 1998;47( 3):405.

6.Tolhurst, Rachel Amekudzi, Yaa Peprah Nyonator, Frank K Bertel Squire,S Theobald, Sally. (2008). “He will ask why the child gets sick so often”: The gendered dynamics of intra-household bargaining over healthcare for children with fever in the Volta region of Ghana. Social Science Medicine, 66(5), 1106.

7.Tolhurst, Rachel Nyonator,Frank K. (2006). Looking within the household: Gender roles and responses to malaria in Ghana. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 100(4), 321.

8.Ghana Demographic and Health Surveys of 1988, 1993, 1998, and 2003

9.United Nations World Population Prospects Report 2006 Revision